Interaction, part 2

Unit Camera Movement

Suppose that we are using the mouse and keyboard callbacks (we’ll combine the two soon). When the mouse is in the left half of the window, a key press or mouse click means “move to the left,” and similarly if the mouse is in the right half of the window. (In the gaming community, this sort of movement is known as strafing.) Also, if the mouse is in the upper half of the window, a key press or mouse click means “move up,” and similarly an action in the lower half means “move down.” Assuming (for the sake of simplicity), that the camera is facing down the $-Z$ axis, how can we implement this sort of movement?

First, we need to know how big the window is, so that we can know where the middle is. Let’s set up global variables to record this. These could be constants, but if we want to allow the user to reshape the window, we would set up a reshape event handler (another DOM event; we’ll leave that aside for now) that would modify these values if the window changes size.

var winWidth = 400;

var winHeight = 200;

Assume that the camera is set up using at and eye points, as we did back

when we learned that API.

var eye = THREE.Vector3(...);

var at = THREE.Vector3(...);

The callback code below uses a coding trick that some of you may not know. It’s the sometimes despised ternary operator. It’s a shorthand for a longer

if ... then .. elseblock, and it returns a value. When used like this, it can replace 7-8 lines of code with just one. Here, the expression

x > 0 ? +1 : -1

means “if x is greater than zero, use +1 as the value, otherwise -1”

Our callback function can then operate as shown below. Note how this enforces our assumption that the camera is always facing parallel to $-Z$.

function onMouseClick (event) {

... // compute (cx,cy)

var x = cx - winWidth/2

var y = winHeight/2 - cy;

moveX( x > 0 ? +1 : - 1);

moveY( y > 0 ? +1 : - 1);

TW.render();

}

function moveX (amount) {

eye.translateX(amount);

at.translateX(amount);

}

function moveZ (amount) {

eye.translateZ(amount);

at.translateZ(amount);

}

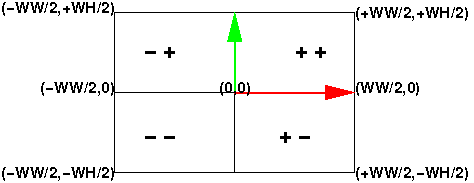

Let’s focus on the first two lines of the callback function. Essentially what we’re doing is mapping to a coordinate system where (0,0) is in the center of the window, $x$ increases to the right and $y$ increases up (whew!). This easily divides the window into the four signed quadrants that we’re used to. See this figure:

We can map the mouse coordinates to a coordinate system where the center is (0,0) and the $x$ coordinate can range from negative half the window width (-WW/2) to positive half the window width (WW/2), and similarly the $y$ coordinate ranges from negative half the window height (-WH/2) to positive half the window height (WH/2).

The rest of the callback is straightforward.

Proportional Camera Movement

In the previous section, we’re throwing away a lot of information when we just use the sign of the mouse coordinates. Why not move the camera a lot if the mouse click is far from the center, but only a little if it is close to the center? That is, we could make the amount of movement proportional to the distance from the center. Now our mouse is becoming useful. Building on the ideas from the previous section, our coding is fairly straightforward.

Recall that the maximum absolute value of the mouse coordinates is half the

window width or height. If someone clicks at the extreme edge and we want that

to result in, say, the camera moving by maxX or maxY units, we can arrange

for that with a straightforward mathematical mapping. We first map the $x$ and

$y$ coordinates onto the range [-1,1] by dividing by their maximum value.

Then, multiply that by the largest amount we would want to move. (Call that

the xSpeed and ySpeed.)

The JavaScript code is as follows:

var xSpeed = 3.0; // just an example

var ySpeed = 4.0; // just an example

function onMouseClick (event) {

... // compute (cx,cy)

var x = cx - winWidth/2

var y = winHeight/2 - cy;

moveX(xSpeed * x/(winWidth/2));

moveY(ySpeed * y/(winHeight/2));

Oh, that’s so much better! We even avoid the ternary operator.

Thus, if the user clicks in the middle of the lower right quadrant (the $+-$

quadrant), $x$ will have a value of $+0.5$ and $y$ will have a value of

$-0.5$, and so moveX will be invoked with 1.5 and moveY with -2.0.

Of course, we’re not limited to a linear proportionality function. If, for example, we used a quadratic function of the distance, mouse clicks near the center could result in slow, fine movements, while clicks far from the center could result in quick, big movements. This could be useful in some applications.

Picking and Projection

So far, our interaction has been only to move the camera, but suppose we want to interact with the objects in the scene. For example, we want to click on a vertex and operate on it (move, delete, inspect, or copy it, or whatever). The notion of “clicking” on a vertex is the crucial part, and is technically known as picking , because we must pick one vertex out of the many vertices in our scene. Once a vertex is picked, we can then operate on it. We can also imagine picking line segments, polygons, whole objects or whatever. For now, let’s imagine we want to pick a vertex.

Picking is hard because the mouse location is given in window coordinates, which are in a 2D coordinate system, no matter how we translate and scale the coordinate system. The objects we want to pick are in our scene, in world coordinates. What connects these two coordinate systems? Projection. The 3D scene is projected to 2D window coordinates when it is rendered.

Actually, the projection is first to normalized device coordinates or NDC. NDC has the x, y, and z coordinates range over [-1,1].

You might wonder about the existence of the z coordinate. Since we’ve projected from 3D to 2D, aren’t all the z values the same? Actually, the projection process retains the information about how far the point is by retaining the z coordinate. The view plane (the near plane) corresponds to an NDC z coordinate of -1, and the far plane to an NDC z coordinate of +1.

The NDC coordinates are important because OpenGL will allow us to unproject a location. To unproject is the reverse of the projection operation. Since projecting takes a point in 3D and determines the 2D point (on the image plane) it projects to, the unproject operation goes from 2D to 3D, finding a point in the view volume that projects to that 2D point.

Obviously, unprojecting an (x,y) location (say, the location of a mouse click) is an under-determined problem, since every point along a whole line from the near plane to the far plane projects to that point. However, we can unproject an (x,y,z) location on the image plane to a point in the view volume. That z value is one we can specify in our code, rather than derive it from the mouse click location.

Suppose we take our mouse click, (mx,my), and unproject two points, one using z=0, corresponding to the near plane, and one using z=1, corresponding to the far plane. (At some point, the API changed from NDC to something similar but with z in [0,1].)

var projector = new THREE.Projector();

var camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera(...);

function pick (mx,my) {

var clickPositionNear = new THREE.Vector3( mx, my, 0 );

var clickPositionFar = new THREE.Vector3( mx, my, 1 );

projector.unprojectVector(clickPositionNear, camera);

projector.unprojectVector(clickPositionFar, camera);

...

}

What this does is take the mouse click location, (mx,my), and find one point

on the near plane and another on the far plane. The Three.js Projector

object’s unprojectVector() method modifies the first argument to unproject

it using the given camera.

Thought question: If we drew a line between those two unprojected points, what would we see? Here’s a demo that does exactly that:

Ray Intersection

Our next step in picking is to take the line between those two points, and

intersect that line with all the objects in the scene. The Three.js library

has a Raycaster object that has a method that will take a point and a vector

and intersect it with a set of objects. It returns a list of all the objects

that the ray intersects, sorted in order of distance from the given point, so

the first element of the returned list is, presumably, the object we want to

pick.

The Three.js library comes with an example that demonstrates this very nicely:

You’re encouraged to look at the code for that example.

The example that allows you to click to create points and click-and-drag to move them employs all of these techniques:

draw moveable points with shift+click

Event Bubbling

In this reading, we’ve always bound the listeners to the document, but if

your graphics application is running in a canvas on a larger page that has

other things going on, you might bind the listener to some parent of the

canvas instead. An issue that can arise is that the other applications may

also bind the document and then both event handlers might get invoked.

This is called event bubbling. If you want to learn more, you might start

with the Quirk Mode page on Event

Bubbling. There are, of

course, other explanations on the web as well.

Source

This page is based on https://cs.wellesley.edu/~cs307/readings/interaction-2.html. Copyright © Scott D. Anderson. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.